Background

Since 2007, indigenous and indigenist organizations working to protect and guarantee the rights of isolated and recently contacted indigenous peoples on the border between Brazil and Peru have carried out many actions to protect these peoples and put pressure on the governments of both countries to integrate their public policies aimed at isolated indigenous peoples.

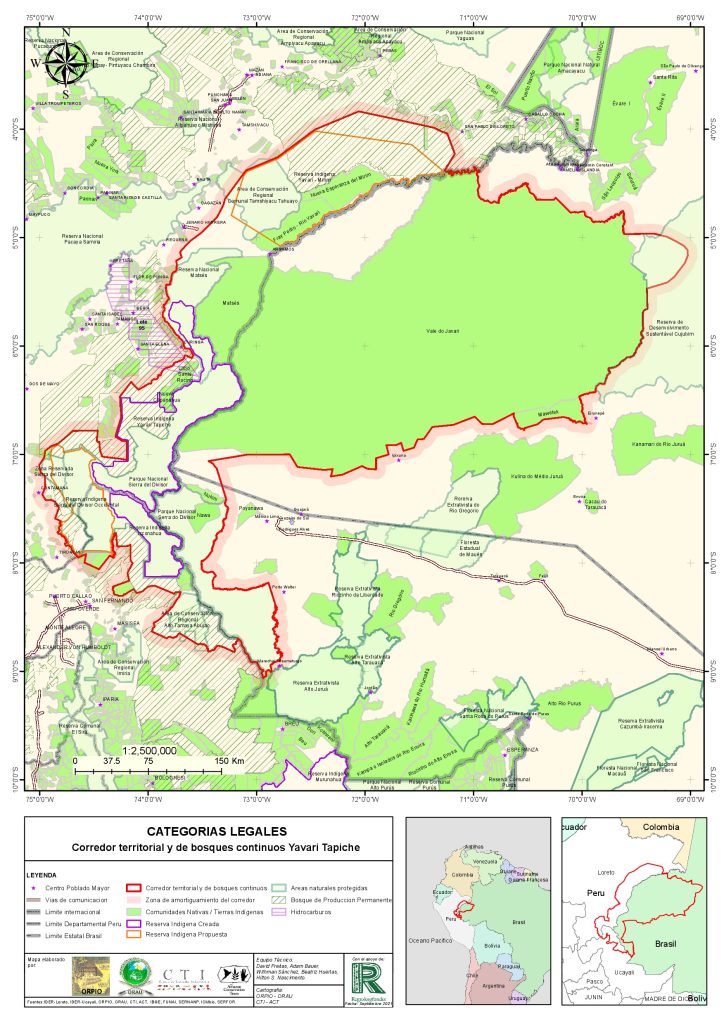

From 2014 onwards, the Organización de Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente (Orpio), an indigenous organization in Peru, with the support of its federations, led a process in partnership with the União dos Povos Indígenas do Vale do Javari (Univaja) and its grassroots organizations to promote the protection and governance of the areas under the action of these organizations – where there is a presence of isolated and recently contacted indigenous peoples. This is how the “Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor of Isolated and Initial Contact Peoples and Continuous Forests” initiative came about.

It is an area of 16,209,966 hectares on the border between Brazil (Amazonas and Acre) and Peru (Loreto and Ucayali). It is generally located in the southern region of the Amazon River, on the interfluve between the Juruá and Ucayali rivers, extending south to the Serra do Divisor region. It is a series of continuous and interrelated territories, inhabited since immemorial times by isolated indigenous peoples and those with recent contact in an uninterrupted manner, constituting the largest area of forest in the world inhabited by peoples with little or no contact with the surrounding society.

This initiative receives the support of partner organizations of the indigenous movement such as the Centro de Trabalho Indigenista (CTI), in Brazil, and has been supported from the beginning by the Rainforest Foundation of Norway (RFN). This is how, in 2021, Orpio and Univaja, together with the CTI and the support of the RFN, drew up the document with the legal, anthropological and environmental foundations that demonstrate the existence of this corridor. The document includes the national and international legal milestones that guarantee the protection of these peoples, details the location and the environmental and socio-economic context of the corridor, the socio-cultural and ethno-historical aspects and the distribution of the various indigenous peoples that inhabit the corridor. This document also deals with the overlapping legal categories, the pressures and threats facing the indigenous territories of the corridor, as well as the actors operating in the region and the initiatives being developed at local, regional and binational level to advance the protection of the rights of isolated and recently contacted indigenous peoples and the governance of this immense territorial corridor.

The indigenous peoples of the Corridor

On the Brazilian side of the territorial corridor, Funai, through its Coordenação Geral de Índios Isolados e de Recente Contato (CGIIRC), officially recognizes at least 17 isolated peoples, probably belonging to the Pano and Katukina linguistic families, but it is not possible to estimate their population size. On the Peruvian side of the corridor, the Matsés, Isconahua (Remo), Kapanawa and other unidentified isolated indigenous peoples are recognized by the Peruvian government.

Three peoples of recent contact also inhabit territories within the Territorial Corridor: the Isconahua, in Peru, and the Korubo and Tyohom-Dyapá, in Brazil, with a total population of around 193 people. The first two belong to the Pano linguistic family and the last to the Katukina family.

In addition to the isolated and recently contacted indigenous peoples, the Territorial Corridor includes, on the Brazilian side, three demarcated Indigenous Lands (TI), the Vale do Javari TI, the Mawetek TI and the Nukini TI, as well as an area in process of being identified, the Nawa TI. These are the Marubo, Mayuruna/Matses, Matis, Kulina-Pano, Nukini and Nawa peoples (of the Pano linguistic family) and the Kanamari (of the Katukina family), with a total population of over 7,500 people. On the Peruvian side, there are 23 native communities (the name given to the indigenous territories recognized by the government of that country), inhabited by around 6,000 indigenous people from the Matses, Kapanawa, Shipibo Konibo and Isconahua peoples (of the Pano linguistic family), the Awajun and Wampis (from the Jívaro linguistic family), the Yagua (from the Peba-Yagua family), the Ashaninka (from the Arawak family) and the Kichwa (from the Amazonian Quechua family).

Indigenous territories

Indigenous territories officially recognized by the respective governments of each of the countries account for 72% of the total area of the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor, with 8.7 million hectares of Indigenous Lands on the Brazilian side (54% of the total) and 2.9 million hectares of Native Communities and Indigenous Reserves for Isolated Indians on the Peruvian side (18% of the total). In the case of the Indigenous Reserves for Isolated Indians in Peru, there is an almost complete overlap with protected natural areas in the corridor.

The protected natural areas

The Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor comprises the area of six protected natural zones, two in Brazil and four in Peru, which cover around 3.1 million hectares and correspond to 20% of the total area of the corridor. In Brazil, it includes the entire Serra do Divisor National Park and a small part of the Cujubim Sustainable Development Reserve. In Peru, it includes the Matsés National Reserve, the Sierra del Divisor National Park, the Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Communal Regional Conservation Area and the Alto Tamaya-Abujao Regional Conservation Area. The area of the Sierra del Divisor National Park in Peru overlaps almost entirely with the three Territorial Reserves created for isolated indigenous people within the corridor: Yavarí Tapiche RI, Isconahua RI and Sierra del Divisor Occidental RI.

Its biodiversity

The corridor involves an area of great biological importance, with high rates of biodiversity. Several environmental surveys carried out in many parts of its area have shown record levels of species diversity, with healthy populations of various animals that, in other places, are at risk of extinction. There are more than 150 species of small, medium and large mammals, making it the area with the greatest diversity of mammals in the world. It has a high diversity of primates, including rare Amazonian species such as the uacari-vermelho and the sagui-de-goeldi, and may be the region with the greatest simultaneous diversity of primates in tropical forests in the world.

It has a highly diverse avifauna, typical of the western Amazon, with more than 580 species of birds, including important migratory birds and species new to science.

Its fish fauna is highly diverse, with more than 500 species estimated, with at least 22 species new to science. It has important ornamental fish communities and a large number of species of economic importance such as pirarucu, aruanã and big migratory catfish.

As far as amphibians are concerned, this is a typical hyperdiverse site in the upper Amazon, with at least seven species new to science.

Its carbon stock

The territorial corridor comprehends areas with the largest carbon stocks in the Amazon, making it a crucially important area for helping to mitigate the effects of climate change worldwide. This situation has led the indigenous peoples who live in the corridor to be harassed by companies dedicated to selling carbon credits, who take advantage of the lack of information and the absence of regulations and consolidated institutions to regulate these operations, guaranteeing the rights of indigenous peoples in the face of contracts that are highly disadvantageous to them.

The threats

Although deforestation in the area of the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor is low, on the Peruvian side, in its western part, forest degradation has been increasing due to the selective extraction of legal and illegal timber and the construction of forest roads to remove these logs.

This logging is a much more serious situation on the Peruvian side of the corridor, where, since 2000, the Peruvian government has granted several concessions for logging, many of them in isolated indigenous territories. After a long legal battle, these concessions were annulled thanks to the work of Orpio. On the Brazilian side, logging has been the main economic activity in the Javari since the 1920s, but after the demarcation of the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, in the early 2000s, this activity became illegal and was practically eradicated. Currently, logging on the Peruvian side ends up affecting areas of Brazil close to the border, with the extraction of Brazilian timber, which is then declared as timber taken from the concessions in Peru.

Another important actor of deforestation in the region is the opening of areas for growing coca to supply drug traffickers. This activity is becoming a major threat to isolated indigenous peoples and could lead to drug traffickers meeting them. Coca cultivation also brings the actions of organized crime to the region, exposing all the indigenous peoples in the corridor to a series of violence associated with this illegal practice.

The intention to open three new roads within the corridor, promoted by the regional governments of Loreto and Ucayali, in Peru, and Acre, in Brazil, would aggravate this situation of deforestation by facilitating the extraction of timber, the expansion of coca cultivation and the invasion into indigenous territories.

On the Peruvian side, the road from Colonia Angamos to Jenaro Herrera, connecting the Javari River to the Ucayali River, and the route from Orellana to Hito 80 both have more localized impacts, but no less significant. The road linking Cruzeiro do Sul, in Acre, with Pucallpa, the capital of the Ucayali department in Peru, has significant regional impacts, cutting through isolated indigenous territories recognized by the Peruvian government, as well as transforming the entire economic and occupation dynamic of the border region to the south of the corridor.

Since the 1930s, and especially in the 1970s, there has been great interest in the oil and gas potential of the regions that make up the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor area, both on the Brazilian and Peruvian sides. From 2007 onwards, an aggressive policy by the Peruvian government began to grant several oil plots in the Amazon region. As a result, six plots, with a total area of 1,600 hectares, were granted by the Peruvian government to explore their potential in areas within the limits of the territorial corridor. From 2012 onwards, the Brazilian side of the corridor also began to be affected by the auctioning of lots for research and subsequent oil exploration, in regions very close to the boundaries of areas used by isolated indigenous peoples.

On the Brazilian side, legal and illegal mining has been getting closer to the territorial corridor from its northeastern part, but specifically from the Jutaí river and tributaries, when this activity began in the region, in the 1980s. In the last decade this activity has begun to expand to other areas such as the Jandiatuba River. This activity can lead to the encounter between miners and isolated indigenous people, leading to conflict. There is even the suspicion of a massacre of a isolated indigenous group by miners on the Jandiatuba river. Mining activity has increasingly been incorporated by organized crime and connected to cross-border mining networks that also operate on the Colombian side of the region. On the Peruvian side of the corridor, illegal mining has moved closer to the boundaries of the Isconahua Indigenous Reserve.

The towns around the Territorial Corridor have a high demand for protein, from the intake of fish (mainly pirarucu), game meat and shellfish (aquatic turtles). A large part of this protein is obtained within the indigenous territories of the Territorial Corridor through the invasion of illegal fishermen and hunters. This activity is based on an old cross-border trade network, which has an estimated production of more than 278 tons/year of game meat sold in the cities of the triple border region, 60% of which is concentrated on the Brazilian side, with the city of Benjamin Constant being its major commercial center. Seizures of canoes with 400 to 700 tracajás caught to supply this demand are recurrent on the region’s rivers.

These invasions bring an escalation of violence in recent years that has never been seen before on the Brazilian side of the corridor, with shooting attacks on Funai’s ethno-environmental protection bases (responsible for controlling the entry and inspection of the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land). This violence culminated in the murders of Funai employee Maxciel dos Santos Pereira, in 2019, Bruno Pereira, a collaborator with the indigenous movement, and English journalist Dom Phillips, in 2022, all of whom were working against this mafia of illegal fishermen and hunters in the region.

This situation leads to a serious risk of these fishermen/hunters meeting isolated indigenous groups as these invaders enter their territories, which can lead to conflicts with deaths and the transmission of diseases. Of the 16 isolated indigenous references recognized by Funai within the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, 13 are at risk of contact and conflict with invading fishermen and hunters. The strong pressure exerted by these fishermen/hunters on the natural resources of the isolated indigenous territories also affects the availability of protein sources for these peoples, which can lead to a situation of food insecurity.

Attempts to forced contact with the isolated indigenous groups that inhabit the territorial corridor have been constantly made by evangelical missionary groups. These missionaries often illegally invade the territories of these isolated peoples and try to co-opt the indigenous communities with the offer of consumer goods and schools, occupying spaces that should be ruled by the respective national states.